Using the find Command Effectively (Part 1)

Contents

What is find for?

When the find command was documented in the 5th Edition Unix

(1974) manual, the usage example shows how to remove files that

match a certain pattern of names and which have not been accessed in a

week. In a later version of the Unix manual, find is used to search

for files in preparation for backing them up with the cpio

utility. The motivation for using find at the time appears to have

been limited disk space on a shared system; find could be used to

identify files to remove or to move off-line. The command itself

originated in a version of Unix called the Programmer’s Workbench or

PWB.

While available disk space is not as much of a concern these days, the

approach find took makes it extremely flexible when locating

files. To paraphrase the POSIX standard: “The find utility shall

recursively descend the directory hierarchy […] evaluating a Boolean

expression […] for each file encountered.” It’s the syntax of the

Boolean expression that gives find its flexibility and also a syntax

that is somewhat unusual for Unix or Linux commands.

find has been part of every Unix or Unix-like operating system since

those early days and is standardized in the POSIX utility

standard. Different versions of find have different features (the

GNU version in particular has a very large number of them.) Where

appropriate, the specific version of find is mentioned in the

examples below. The goal of this post is not to be comprehensive, but

to show find fundamentals and effective usage.

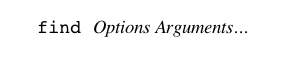

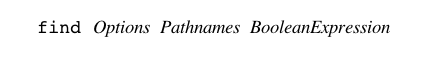

Basic Structure of the Command

The example in the early Unix manual page for find to remove old

files looks somewhat complicated:

find / "(" -name a.out -o -name "*.o" ")" -a -atime +7 -a -exec rm {} ";"

The basic structure of the find command is not fundamentally

different from most other command line utilities though.

Arguments are made up of pathnames and the Boolean expression.

Following this pattern, one can see the following for the example above:

- No options are specified

- The pathname from which to start searching is

/ - The Boolean expression is

( -name a.out -o -name *.o ) -a -atime +7 -a -exec rm {} ; - Parts of the expression are quoted with

"because certain characters have special meaning to the shell

Tests, Actions, and Boolean Operators

find will start at the pathname listed on the command line, descend

into all accessible directories below it, and then for each file

evaluate the Boolean expression. The expression is made up of tests

(e.g., what is the name of the file? What size is it?) and actions

(e.g., output the file’s pathname) that are tied together with Boolean

operators. Tests and actions together are referred to as “primaries.”

Primaries and operators look like options, they start with a -.

Pathnames

findsupports more than one pathname from which to start searching. Usefind dir1 dir2 ...to search through bothdir1anddir2in sequence. No loop is necessary.

Boolean Operators

The Boolean expression is made up of primaries connected with

operators. The logical AND is implicit and it is unnecessary to

write the -a.

| Operator | Logical Function | Alternate names |

|---|---|---|

( ) |

Group expression | |

! |

NOT |

-not |

-a |

AND |

blank, -and |

-o |

OR |

-or |

The example uses expression grouping, AND, and OR:

( -name a.out -o -name *.o ) -a -atime +7 -a -exec rm {} ;

Each test (in this case -name and -atime) has a truth

value. Because actions (here -exec) are also part of the Boolean

expression, it is tempting to read this expression as an if-then,

which is incorrect. An action also has a truth value, in the case of

-exec the exit code of the command invoked. It might be more useful

to consider an action a test with a side effect.

Boolean operators in find use short-circuiting, which means that

only as many primaries are executed as are necessary to know the value

of the expression. In the example, only when -name a.out -o -name

*.o is true the -atime test will be executed. Only if either of

the name tests and the -atime (file access time) test yield true,

the -exec action will be executed.

The GNU version of find also offers the , operator to sequence

primaries independent of their outcome.

Two implicit defaults in find simplify the Boolean expressions:

-ais implied if no is operator used- The

-printaction is the default if no other output action is specified

In practice this means, for example, to simply print all file

pathnames for files that end with .o and are greater than 1MB in

size, all that is necessary is:

find . -name *.o -size +1M

The -name and -size tests are connected with an implicit -a and

the action is the default -print.

Quoting

Note that when using filename patterns quoting will be necessary, otherwise the shell will attempt to expand the

*, which will most likely result in an error. The same is true for the parentheses which usually start a sub-shell. For shells that use!for history expansion, it may not be necessary to quote!because it will be followed by a blank.It is not possible to simply wrap the entire expression in

"-quotes becausefindexpects each primary and operator as a separate command argument.

If the goal is to match files that end in .o or are greater than 1MB

in size, the command is:

find . -name *.o -o -size +1M

A way to visualize the implicit -print is as if it wrapped the

entire Boolean in parentheses:

find . ( -name *.o -o -size +1M ) -a -print

There are cases in which the final -print is not desired when the

Boolean expression succeeds and explicitly using -print is

necessary.

Many find versions also have a -true and a -false primary

available that can help with complicated Boolean expressions.

Tests

Different find version have many different tests. The GNU version is

particularly extensive and its Info manual breaks down the tests into

easy to understand categories. POSIX supports many fewer tests and

most of those are explained here. Less common tests like -links are

not discussed.

To structure an effective Boolean expression for find, reduce the

number of files to be processed as early a possible in the

expression to take advantage of the short-circuiting. Testing for file

type or owner if known is an easy way to reduce the number of further

tests and actions.

Names

-name,-iname-path,-ipath

The -name test has already been mentioned before and it takes a

filename pattern. A common extension is -iname for case-independent

matching of the filename. The -path test checks the entire pathname

including the search starting point specified on the command line.

Times

-atime,-mtime,-ctime-amin,-mmin,-cmin-newer

Using find with file times is complicated and tends to be

surprising. The file times that can be tested depend on what the

system supports and usually is file access time -atime, file

modification time -mtime, and file metadata change time -ctime

(macOS for example also supports file creation time.)

The time to test for can either be an exact number, less than a

number, or greater than a number. The time is 24 hour intervals

rounded down: -atime -2 means file access of less than 48 hours,

-atime 0 means file access within the last 24 hours, and -atime +7

(the test from the example) means file access more than 168 hours ago.

Because it is often necessary to find files with time stamps of finer

granularity, most modern find implementation also support minute

ranges and time suffixes for the standard time tests like -mtime

-1h30m.

-daystart

The GNU version of

findhas an option called-daystartwhich changes the meaning of time tests from 24 hour periods to times relative to the current day. Therefore-mtime 1simply means “yesterday.”This option behaves differently from other options in that it can appear anywhere within the Boolean expression and only affects tests following it.

The -newer test takes a file name as a parameter and tests if the

current file has a modification newer than that file. Because touch

can set arbitrary modification times on files, this is an easy way to

test file times relative to a given timestamp. POSIX only specifies

modification times, but other versions of find can also check other

timestamps.

Size

-size

The -size test has been mentioned before and has two unexpected

behaviors:

- The default unit is 512 bytes

- Sizes are rounded by unit given

POSIX only supports either 512-byte blocks or the c suffix for

bytes. Other implementation use suffixes like k, M, or G for kB,

MB, or GB (strictly, these are base-2 powers, so k stands for 1024

bytes or a KiB.)

The rounding of GNU find has an interesting side effect. If the goal

is to search for files between 512k and 1M, the logical approach would

be: find . -size +512k -size -1M. This does not work for GNU find

(it does work in BSD find) because -1M means less than one and

that is zero. In other words, it tries to find files that are zero

bytes in length but also greater than 512k. The workaround for this is

to use the next smaller unit: find . -size +512k -size -1024k.

When not using units, but 512-byte blocks as defined in POSIX, the

size of the file tested is rounded up to the next 512-byte boundary,

which means that to find a file that is more that 2KB but less than

3KB, a find . -size +4 -size -7 is required.

Type

-type

The -type test expects a character to represent the file type as a

parameter. Commonly used ones are f for a regular file, d for a

directory, and l for a symbolic link, similar to the output of ls

-l. GNU find allows multiple file types separated by comma.

Owner

-user,-group-nouser,-nogroup

The file’s owner or group are tested against the parameter given,

which can be a user or group name or a UID/GID. The -no variants

test if the UID or GID for the file has no user or group associated

with it.

Permissions

-perm

Testing permissions (or more generally mode bits of files) using

numeric values is syntactically straightforward. It uses the same

octal representation as chmod and umask.

-perm 644 |

Test for exactly user rw, group r and other r |

-perm -400 |

Test for user r, anything else doesn’t matter |

-perm -440 |

Test for user and group r, anything else doesn’t matter |

-perm +440 (BSD) or -perm /440 (GNU) |

Test for user and/or group r, anything else doesn’t matter |

Using the symbolic mode syntax (which is derived from chmod) is

notoriously easy to get wrong. The pattern to test against is built up

by adding to and removing bits from an initially empty bit mask.

The pattern rw-r--r-- can be created with any of these combinations:

u=rw,go=r |

User rw, group and other r |

a=r,u+w |

All r, add w to user |

a=rw,go-w |

All rw, remove w from group and other |

| etc. |

More commonly, the desired test is for a combination of bits and not

the exact permission, which is where the leading - comes in. The

equivalent of -400 (does the user have read permission?) is more

readable as -u=r

Testing for permissions not set cannot be done with a mode bit mask,

but with the ! Boolean operator: ! -perm -u=w tests if the file

owner is lacking write permissions.

Coming Up…

Once find locates the right files, acting upon them is the next

step. The implicit -print and the -exec action were already

mentioned and in the next post actions will be considered in more

detail. Options that change how find traverse the file system are

discussed and some additional examples will be explained.